Understanding Arguments

What is an Argument?

An argument is the smallest meaningful component within an argument map. It is an assertion that has been made (e.g., by a person or an organization). Some arguments are written by Controvis users to summarise an interesting assertion or group of assertions. Others are direct-quotes from a source. Quotes contain sources, with links (where possible) to source webpages and metadata pages containing additional contextual information about speakers and authors.

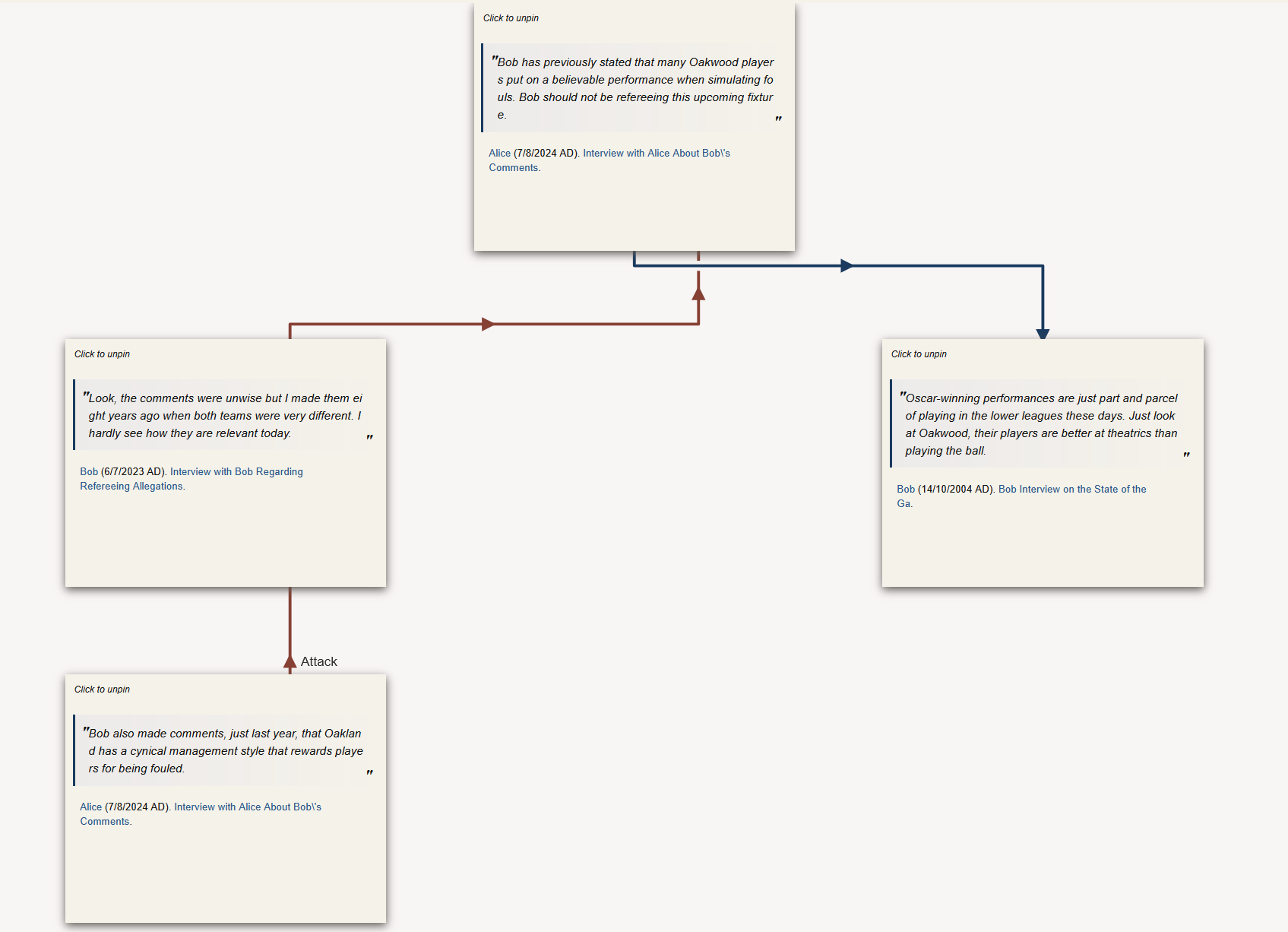

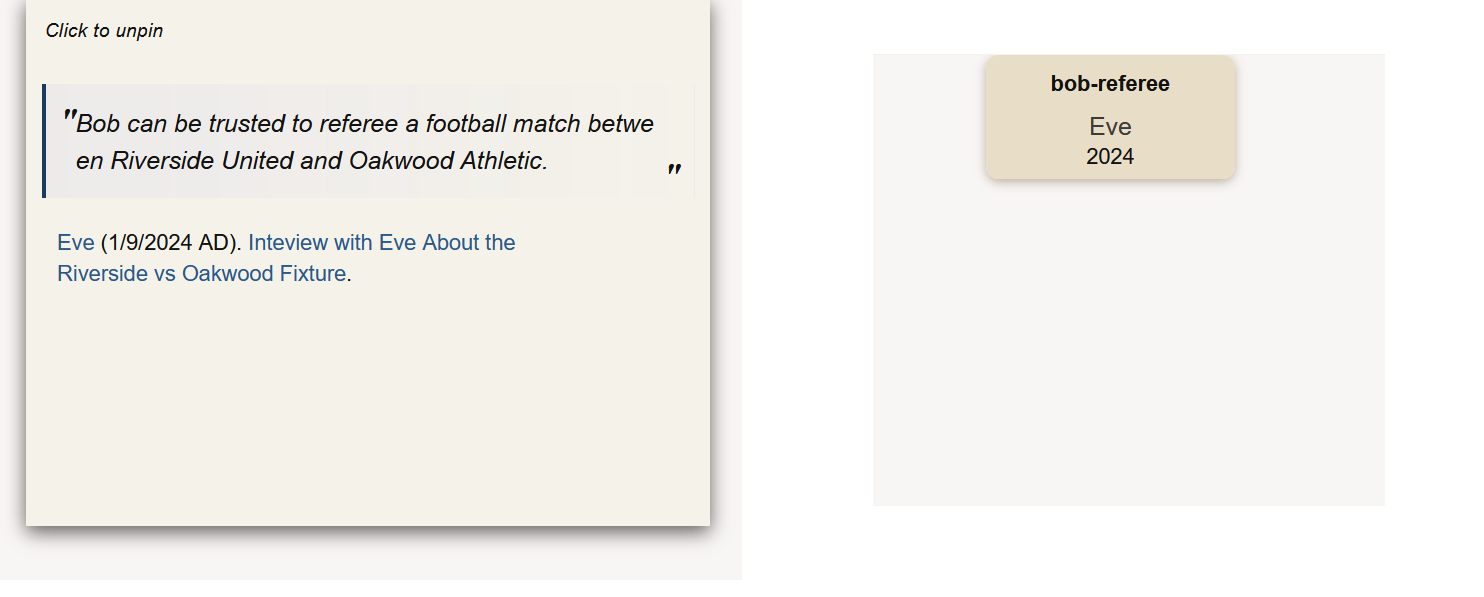

Argument Visualization

Arguments can appear in two formats on the map:

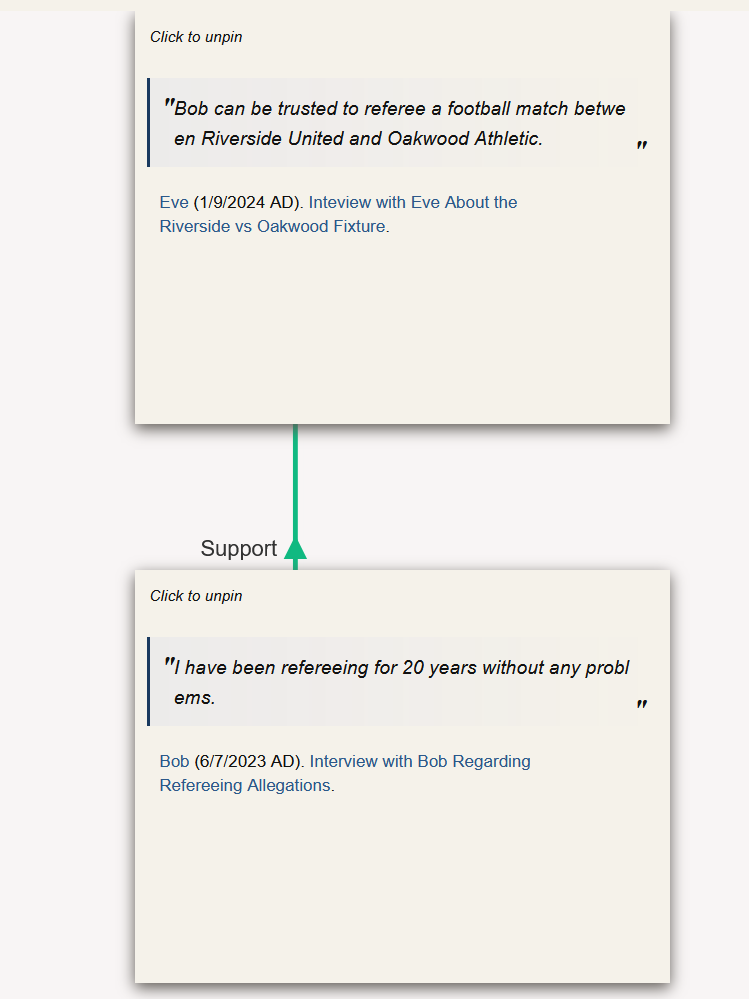

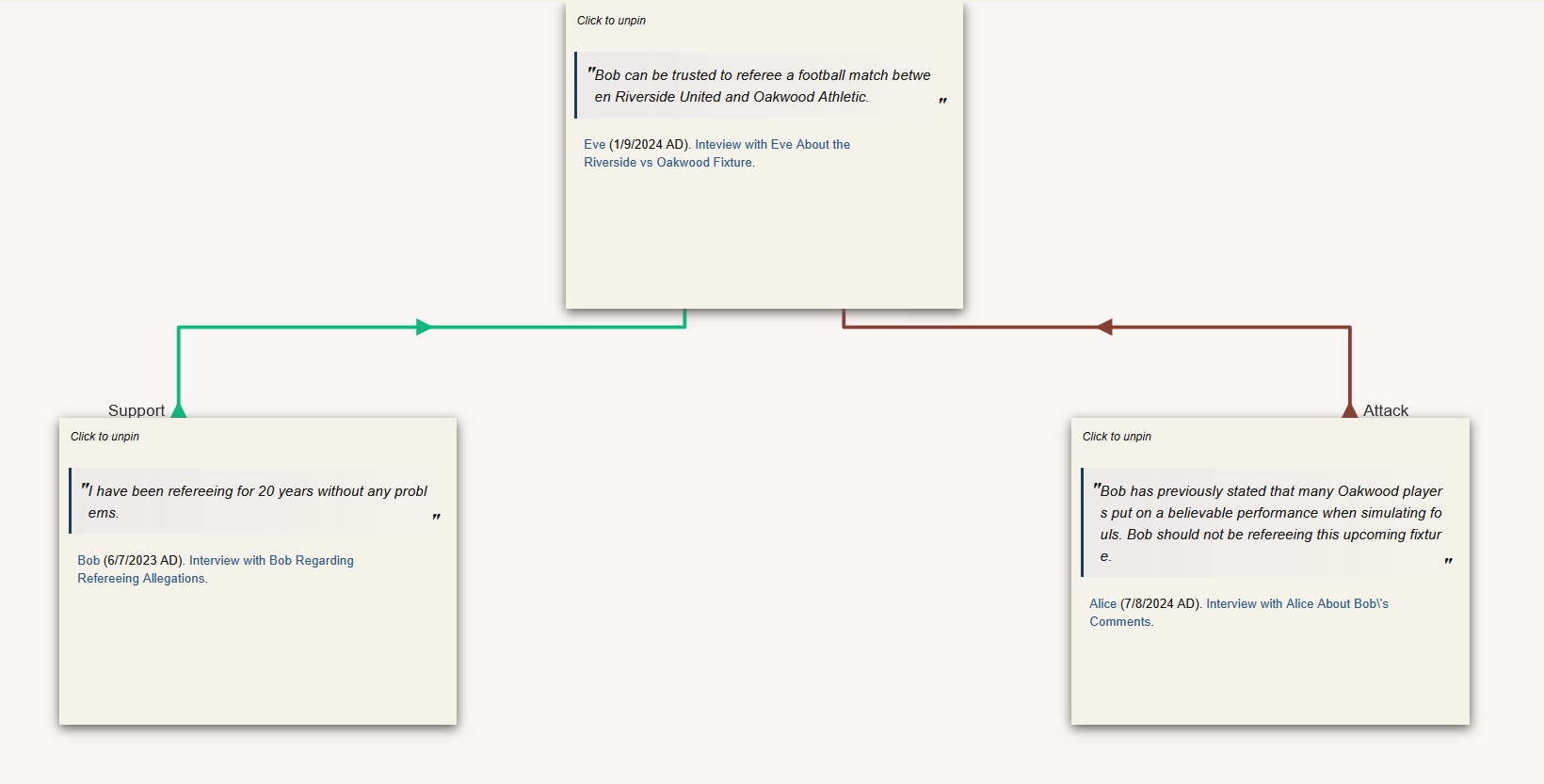

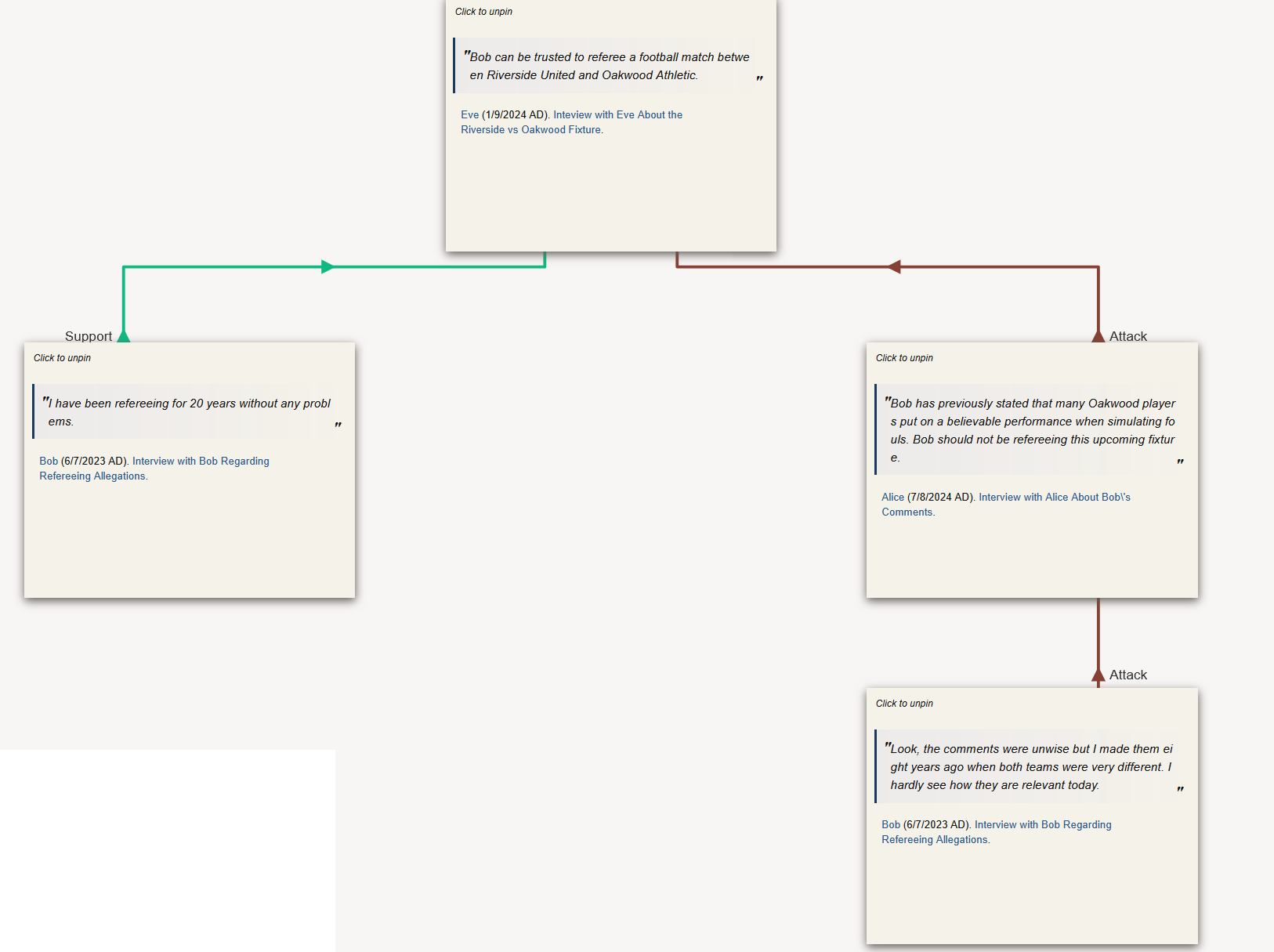

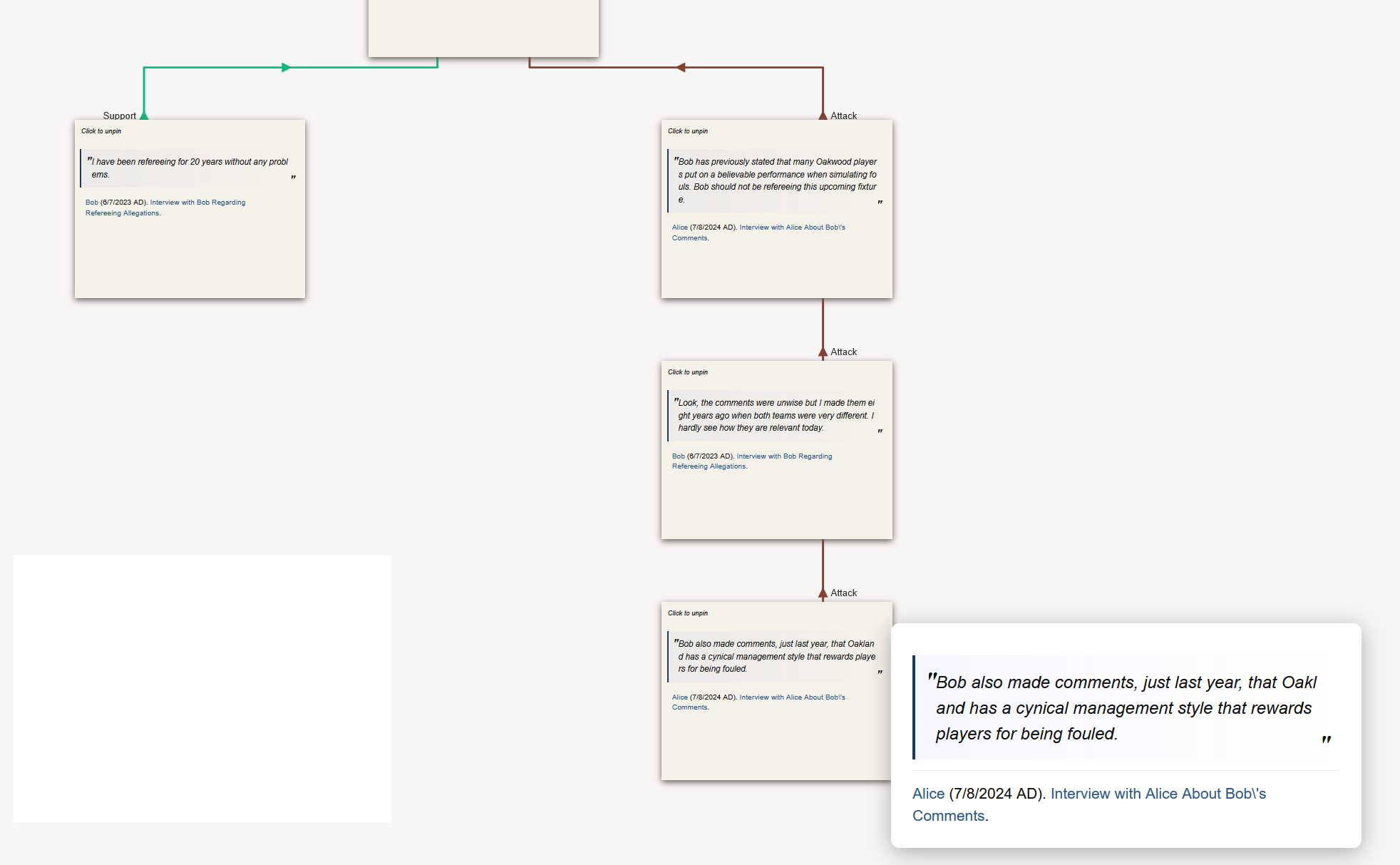

- Pinned (expanded view) - Displays the full text of the argument, allowing you to read the content directly.

- Unpinned (collapsed view) - Represented as a small box with tags, which helps simplify complex maps while preserving all arguments.